There’s a deep-rooted belief in youth sport that training should leave you sore, red faced and out of breath. A belief that the fittest athlete reigns supreme, and therefore sees every young athlete flogging their body.

But while fitness is important, it’s not what separates the best from the rest. Anyone can sweat. You just lace up, and go. The real distinguishing factor is skill. And skill is much harder to develop.

“We still have it in the All Blacks, guys who come in who are great at ‘sweating’ but not very good at improving their skill.”

– Nicholas Gill, All Blacks Strength & Conditioning Coach

True skill is the ability of the performer to apply their behaviour with maximum certainty in a variety of contexts and situations. For example, a skillful basketballer continues to hit 3-pointers when she’s tired, the scores are tied, and the game’s in the dying seconds of the final quarter. A skillful rugby player catches the high ball every time, even when it’s cold, wet, and an opposition tackler is headed straight for him. And a skillful golfer sinks the long putt for a birdie on the 18th green when the national championship is on the line. True skill is characterised by its adaptability and certainty of outcome; but to be skillful, you must move with technical and psychological efficiency.

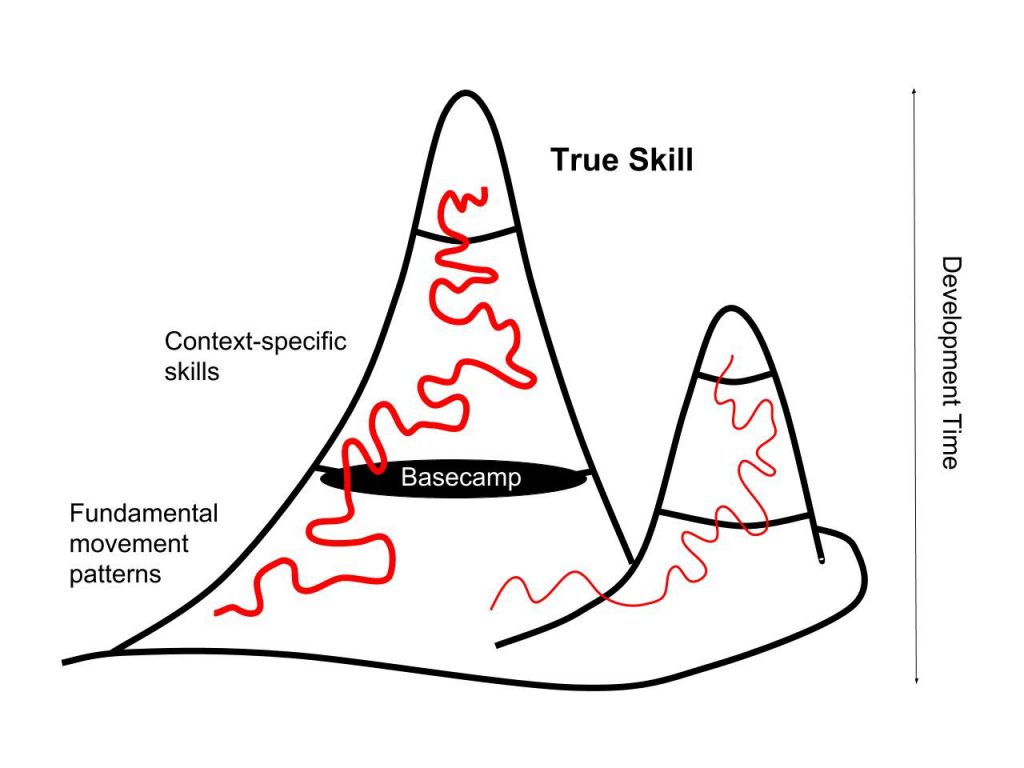

The Mountain of Movement Development

Developing movement skill is a sequential process. To reach higher levels of motor skill, particularly when the goal is to become an adaptable performer, solid foundations are essential. Why? Because without them, while you might be able to perform a skill in training, or against a weaker opposition, when the pressure comes on and it really matters, your skill will break down.

Consider, if you will, the development of movement skill like learning to climb a mountain. As Jane Clarke and Jason Metcalf described in their 2002 book, Motor Development: Research and reviews:

“Climbing the mountain of motor development is an apt metaphor in that it takes years to learn, embodies and inherently sequential and cumulative process, and is influenced by individual skills and abilities as well as individual differences in context and practice. It is also representative of the ultimate accomplishment of motor development (the peak of the mountain), that is, the attainment of skilled motor action.”

In their mountain of motor development metaphor, Clark and Metcalf (1994) identified 5 major periods of development. Given my focus on youth sport, in this article I will only discuss the 3 most advanced developmental periods; fundamental movement patterns, context-specific movements patterns, and true skill (figure 1). These periods coincide with the years from early childhood to late adolescence.

Figure 1. The Mountain of Movement Development

Fundamental Movement Patterns

The fundamental movement patterns period begins 3 months after a child takes their first steps, although progress continues for several years. It is the period during which the “building blocks” of sport-specific skill are developed. For instance, a child learns to hop, skip, and jump during this period, as well as to catch, pass and strike. Ideally, a diverse repertoire of movement skill is developed during this period so that a child can pick up more complex sports skills in a variety of specific movement contexts in later years.

The shift into the next development period begins when a child has a specific reason to move, which for a young athlete, can occur anywhere from 4 to 10 years of age. This transitional phase can be considered a child’s movement “basecamp” – a phase that will be returned to when a movement ‘roadblock’ is experienced. For example, significant injury.

Context-Specific Skills

Context-Specific Skills

During the context-specific period, the development of movement skill becomes increasingly specific to the sports in which the athlete participates. For example, jumping will become rebounding for the young netballer, and throwing will become bowling for the young cricketer. Crucially, the goal of the context-specific period is to learn how to adaptively apply fundamental movement patterns to a variety of “constrained” situations. For example, in beach volleyball, to perform a well-executed hit over the net (i.e., a context-specific skill of the game), jumping and striking (e.g., two fundamental movement patterns) must be effectively adapted by the player.

It is during this period that an athlete must traverse the mountain according to their individual skill level and specific sporting requirements. At any point in time, a young athlete may reach one level of the mountain in one sport, while a completely different level in another. Alternatively, an athlete may face a movement obstacle in one sport that forces them down the mountain to recalibrate a fundamental pattern at basecamp, before heading back up the mountain as a more skilled mountaineer. Take rebounding in netball, for example. To execute a skilled rebound (i.e., one that is performed to the athlete’s best ability and with a level of competency that limits injury) the athlete must first be able to execute a skilled jump and landing.

True Skill

While true skill is every athlete’s utopia, the inherent challenges of climbing a mountain prevent most from ever making it. To further explore the mountain metaphor, the level of success attained (i.e., how close an athlete gets to true skill) is highly specific to the characteristics of the mountain, the environment conditions on the mountain, and the individual skills and abilities of the mountaineer. In other words, every athlete’s climb is unique based on their individual choices and circumstances, with the only certainty being obstacles faced along the way. Therefore, the goal should not be to get to the top but to ‘climb the mountain’. Attention should be directed towards the long-term process of acquiring adaptive and skilled performance, rather than the outcome.

Be the best you can be,